Medical or dental practitioner acting as locum tenens

FREE

Ask the similar questions

Medical or dental practitioner acting as locum tenens

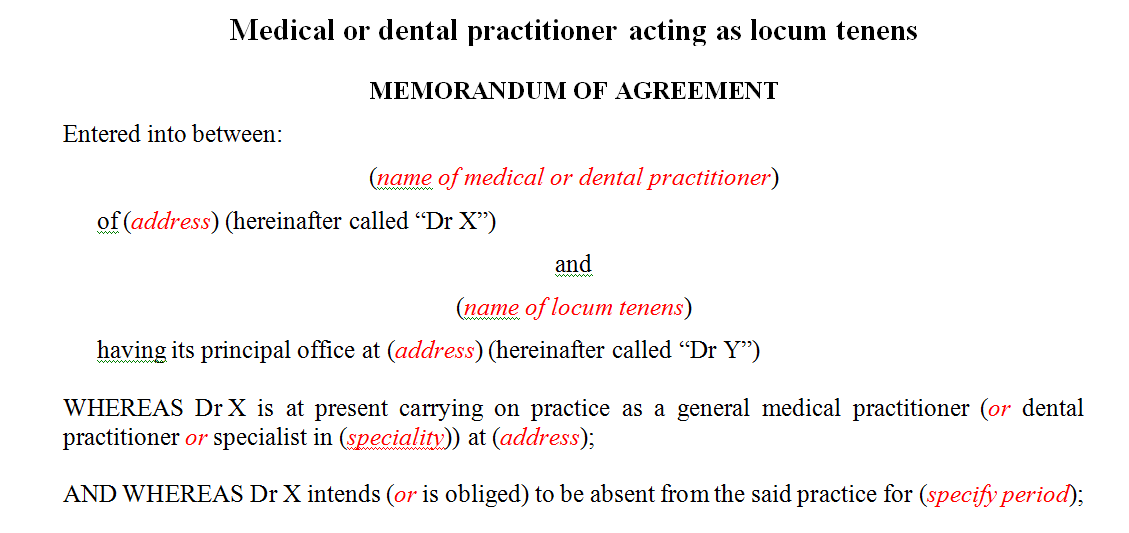

Medical or Dental Practitioner Acting as Locum Tenens

Agreement between the dental practitioner and a temporary substitute doctor detailing the details of this agreement.

Many medical practitioners in private practice use a locum tenens when they themselves are not available to practice. The locums are often appointed without consideration of the legal consequences or requirements.

The words locum tenens originate from Latin meaning "one holding a place". The designation was used by doctors ("principals") who needed a person to temporarily fill their positions, should they not be available for a short period of time.

Today locum tenens are in demand nearly everywhere, whether in a city or a small town, when a doctor is not personally available to practice.

Legislation distinguishes between an employee and an independent contractor. If the locum is appointed as an employee the doctrine of vicarious liability comes into play which is not the case with an independent contractor. Contracts currently available to appoint a locum give the contracting parties a choice between being appointed as an employee or an independent contractor; this should be changed in that all locums should be appointed as independent contractors especially if the working of the Consumer Protection Act is also taken into consideration.

Furthermore, according to the rules of the Health Professions Council of South Africa (HPCSA) the onus to ensure that the locum tenens is registered and fit to practice, rests with the principal.

Doctors in private practice may make use of a locum for several Reasons, including:

• to take study leave or acquire new skills;

• to attend foreign or local congresses; or

• for vacation leave.

It is not always possible to fill these gaps internally and hence the need for locums. Most of the time locums are appointed by medical practitioners without thinking of the legal consequences of the appointment.

In legal terms when something goes wrong either with a patient or with the practice, it is very important to establish whether a locum was appointed as an employee or as an independent contractor for the period that he or she has to stand in for the principal.

If a locum is appointed as an employee, the rights of employees under the Labour Relations Act and the Basic Conditions of Employment Act could come into play depending on the amount of remuneration the locum will receive.

A further aspect to take note of when appointing a locum as an employee is the possible application of the doctrine of vicarious liability, according to which the medical practitioner himself or herself could be held liable for the unlawful and/or negligent conduct of the locum. This danger exists to a lesser extend if a locum is appointed as an independent contractor, as vicarious liability will be applicable only if the doctor appointed an incompetent locum or where a locums actions caused prejudice to third parties.

Two pro forma contracts that a medical practitioner in private practice appointing a locum himself or herself can use are included. These contracts are analysed and recommendations are made to improve the current options to the benefit of both parties.

A medical practitioner can also make use of an agency or a temporary employment service to provide the practice with a locum for the period he or she will not be available. The legal consequences in this regard are highlighted only to the extent that they overlap with the test of an employee-employer relationship, but on a different level.

Neither of the two pro forma contracts addresses the effect of the Consumer Protection Act on the medical profession. This aspect is discussed very briefly, mainly to indicate the role of the locum in the application of the Act in a medical context and how it should be contractually addressed.

The Health Professions Act 56 of 1974

The Health Professions Act does not address the appointment of a locum directly; neither does the Act indicate whether a locum should be appointed as an employee or an independent contractor.

Section 9 of the Ethical Rules of Conduct for Practitioners registered under the Health Professions Act, 1974 determines the following regarding locums, without prescribing that the appointment of the locum should either be as an employee or as an independent contractor:

• A practitioner shall employ as a professional assistant or locum tenens, or in any other contractual capacity and, in the case of locum tenens for a period not exceeding six months, only a person –

(a) who is registered under the Act to practise;

(b) whose name currently appears on the register kept by the registrar in terms of section 18 of the Act; and

(c) who is not suspended from practising his or her profession.

The locum should also be registered as a health practitioner with the Health Professions Council of South Africa (HPCSA) and the contract of appointment should be in writing. If a member of the HPCSA would like to see such a contract of appointment, it should be available. Thus, neither the Act nor the Ethical Rules prescribes how a locum should be appointed; as an employee or an independent contractor.

It is up to the medical practitioner (principal) and the locum to determine the contents of the contract of employment. The important reason to distinguish between an employee and an independent contractor is because the law attaches different consequences to either appointment. If a locum is appointed as an employee, labour legislation will be applicable to the contract of employment, which will not be the case where an independent contractor is involved.

It is interesting to note that in the Notice concerning the conditions of employment of dental technicians who are employees section 1 describes a locum tenens as "an employee who is employed to relieve a regular employee or dental technician contractor for any period during which a regular employee or dental technician is absent, on sick or other leave”.

Disciplinary action by the HPCSA has been taken against some medical practitioners who allowed unqualified or unregistered persons to act as locum tenens (whether appointed as employees or independent contractors), resulting in hefty fines and/or temporary suspension. Medical practitioners should accordingly also take care when appointing locums to ensure that they are duly qualified and registered.

If no contract was concluded stipulating whether the locum is an employee or an independent contractor, this complicates matters if a dispute arises. In such an instance the courts will fall back on the reality test to determine the position of the locum. The reality test is the test currently applied by the courts to determine whether an employee or an independent contractor is involved in a dispute.

Employee or independent contractor?

Common law

The common law views a contract of employment as an ordinary contract between two parties. It further treats a service contract as a subdivision of a contract of lease.

Common law defines a contract of employment as an agreement between two parties in terms of which one of the parties (the employee) undertakes to place his or her personal services at the disposal of the other party (the employer) for an indefinite or determined period, in return for a fixed or ascertainable remuneration and which entitles the employer to define the employees duties and to control the manner in which the employee discharges them.

A contract for a certain type of work for a specified time is defined as a reciprocal contract between an employer and an independent contractor. An individual contract of employment commences when the parties agree to the essential terms in the contract and the contract complies with the general requirements for a valid contract, namely:

• there must be consensus between the parties;

• both parties must have contractual capacity;

• the rights and duties stipulated in the contract must be possible to perform;

• the rights created and duties assumed must be permitted by law; and

• the formalities, if prescribed, must be adhered to.

It might not be clear whether the contract between the parties is an employer-employee contract or a contract between an employer and an independent contractor.

The Reality Test

The reality test was first described in the case of Denel (Pty) Ltd v Gerber and has since been expanded upon and confirmed in other cases.

If the contract between the medical practitioner and the locum stipulates that it is a contract of employment and the locum is therefore considered an employee of the principal, the reality test will not be necessary. It will be relevant only if there is either no written contract (or the contract is unlawful in terms of the HPCSA rules) or where the parties dispute their relationship. As stated earlier it is important to determine the basis of the relationship between a practitioner and locum as labour laws apply only to employers and employees and not to an independent contractor.

If ever a locum is used in a private medical practice, the medical practitioner/s (principal) should ascertain that patients are informed that the locum is a substitute of the physician and not an employee, if that is the case. This could be managed by the receptionist when the patient signs a consent form, and it should be noted on the report by the locum when he or she actually sees the patient.

In all cases it would be better for the practitioner to appoint a locum as an independent contractor, because the locum himself or herself would then be held liable for the alleged unlawful or unprofessional conduct. An independent contractor would have to face cases of delictual negligence on his or her own whereas the employee is "covered" by vicarious liability. The application of the CPA should also be addressed contractually to the benefit of both the principal and the locum.

Agreement between the dental practitioner and a temporary substitute doctor detailing the details of this agreement.

Many medical practitioners in private practice use a locum tenens when they themselves are not available to practice. The locums are often appointed without consideration of the legal consequences or requirements.

The words locum tenens originate from Latin meaning "one holding a place". The designation was used by doctors ("principals") who needed a person to temporarily fill their positions, should they not be available for a short period of time.

Today locum tenens are in demand nearly everywhere, whether in a city or a small town, when a doctor is not personally available to practice.

Legislation distinguishes between an employee and an independent contractor. If the locum is appointed as an employee the doctrine of vicarious liability comes into play which is not the case with an independent contractor. Contracts currently available to appoint a locum give the contracting parties a choice between being appointed as an employee or an independent contractor; this should be changed in that all locums should be appointed as independent contractors especially if the working of the Consumer Protection Act is also taken into consideration.

Furthermore, according to the rules of the Health Professions Council of South Africa (HPCSA) the onus to ensure that the locum tenens is registered and fit to practice, rests with the principal.

Doctors in private practice may make use of a locum for several Reasons, including:

• to take study leave or acquire new skills;

• to attend foreign or local congresses; or

• for vacation leave.

It is not always possible to fill these gaps internally and hence the need for locums. Most of the time locums are appointed by medical practitioners without thinking of the legal consequences of the appointment.

In legal terms when something goes wrong either with a patient or with the practice, it is very important to establish whether a locum was appointed as an employee or as an independent contractor for the period that he or she has to stand in for the principal.

If a locum is appointed as an employee, the rights of employees under the Labour Relations Act and the Basic Conditions of Employment Act could come into play depending on the amount of remuneration the locum will receive.

A further aspect to take note of when appointing a locum as an employee is the possible application of the doctrine of vicarious liability, according to which the medical practitioner himself or herself could be held liable for the unlawful and/or negligent conduct of the locum. This danger exists to a lesser extend if a locum is appointed as an independent contractor, as vicarious liability will be applicable only if the doctor appointed an incompetent locum or where a locums actions caused prejudice to third parties.

Two pro forma contracts that a medical practitioner in private practice appointing a locum himself or herself can use are included. These contracts are analysed and recommendations are made to improve the current options to the benefit of both parties.

A medical practitioner can also make use of an agency or a temporary employment service to provide the practice with a locum for the period he or she will not be available. The legal consequences in this regard are highlighted only to the extent that they overlap with the test of an employee-employer relationship, but on a different level.

Neither of the two pro forma contracts addresses the effect of the Consumer Protection Act on the medical profession. This aspect is discussed very briefly, mainly to indicate the role of the locum in the application of the Act in a medical context and how it should be contractually addressed.

The Health Professions Act 56 of 1974

The Health Professions Act does not address the appointment of a locum directly; neither does the Act indicate whether a locum should be appointed as an employee or an independent contractor.

Section 9 of the Ethical Rules of Conduct for Practitioners registered under the Health Professions Act, 1974 determines the following regarding locums, without prescribing that the appointment of the locum should either be as an employee or as an independent contractor:

• A practitioner shall employ as a professional assistant or locum tenens, or in any other contractual capacity and, in the case of locum tenens for a period not exceeding six months, only a person –

(a) who is registered under the Act to practise;

(b) whose name currently appears on the register kept by the registrar in terms of section 18 of the Act; and

(c) who is not suspended from practising his or her profession.

The locum should also be registered as a health practitioner with the Health Professions Council of South Africa (HPCSA) and the contract of appointment should be in writing. If a member of the HPCSA would like to see such a contract of appointment, it should be available. Thus, neither the Act nor the Ethical Rules prescribes how a locum should be appointed; as an employee or an independent contractor.

It is up to the medical practitioner (principal) and the locum to determine the contents of the contract of employment. The important reason to distinguish between an employee and an independent contractor is because the law attaches different consequences to either appointment. If a locum is appointed as an employee, labour legislation will be applicable to the contract of employment, which will not be the case where an independent contractor is involved.

It is interesting to note that in the Notice concerning the conditions of employment of dental technicians who are employees section 1 describes a locum tenens as "an employee who is employed to relieve a regular employee or dental technician contractor for any period during which a regular employee or dental technician is absent, on sick or other leave”.

Disciplinary action by the HPCSA has been taken against some medical practitioners who allowed unqualified or unregistered persons to act as locum tenens (whether appointed as employees or independent contractors), resulting in hefty fines and/or temporary suspension. Medical practitioners should accordingly also take care when appointing locums to ensure that they are duly qualified and registered.

If no contract was concluded stipulating whether the locum is an employee or an independent contractor, this complicates matters if a dispute arises. In such an instance the courts will fall back on the reality test to determine the position of the locum. The reality test is the test currently applied by the courts to determine whether an employee or an independent contractor is involved in a dispute.

Employee or independent contractor?

Common law

The common law views a contract of employment as an ordinary contract between two parties. It further treats a service contract as a subdivision of a contract of lease.

Common law defines a contract of employment as an agreement between two parties in terms of which one of the parties (the employee) undertakes to place his or her personal services at the disposal of the other party (the employer) for an indefinite or determined period, in return for a fixed or ascertainable remuneration and which entitles the employer to define the employees duties and to control the manner in which the employee discharges them.

A contract for a certain type of work for a specified time is defined as a reciprocal contract between an employer and an independent contractor. An individual contract of employment commences when the parties agree to the essential terms in the contract and the contract complies with the general requirements for a valid contract, namely:

• there must be consensus between the parties;

• both parties must have contractual capacity;

• the rights and duties stipulated in the contract must be possible to perform;

• the rights created and duties assumed must be permitted by law; and

• the formalities, if prescribed, must be adhered to.

It might not be clear whether the contract between the parties is an employer-employee contract or a contract between an employer and an independent contractor.

The Reality Test

The reality test was first described in the case of Denel (Pty) Ltd v Gerber and has since been expanded upon and confirmed in other cases.

If the contract between the medical practitioner and the locum stipulates that it is a contract of employment and the locum is therefore considered an employee of the principal, the reality test will not be necessary. It will be relevant only if there is either no written contract (or the contract is unlawful in terms of the HPCSA rules) or where the parties dispute their relationship. As stated earlier it is important to determine the basis of the relationship between a practitioner and locum as labour laws apply only to employers and employees and not to an independent contractor.

If ever a locum is used in a private medical practice, the medical practitioner/s (principal) should ascertain that patients are informed that the locum is a substitute of the physician and not an employee, if that is the case. This could be managed by the receptionist when the patient signs a consent form, and it should be noted on the report by the locum when he or she actually sees the patient.

In all cases it would be better for the practitioner to appoint a locum as an independent contractor, because the locum himself or herself would then be held liable for the alleged unlawful or unprofessional conduct. An independent contractor would have to face cases of delictual negligence on his or her own whereas the employee is "covered" by vicarious liability. The application of the CPA should also be addressed contractually to the benefit of both the principal and the locum.